A “story arc” refers to stories’ plot structures—how the narrative builds, crests, and then falls again over the course of a plot. Every engaging story has some sort of arc, with the action or tension rising gradually over the story (whether it be a novel, short story, or memoir) before the action falls again as the story’s plot is resolved.

Popular narrative structures include the three-act structure, the five-act structure, and the eight-point arc. Today, we’ll talk about writing an eight-point story.

What is the eight point story arc?

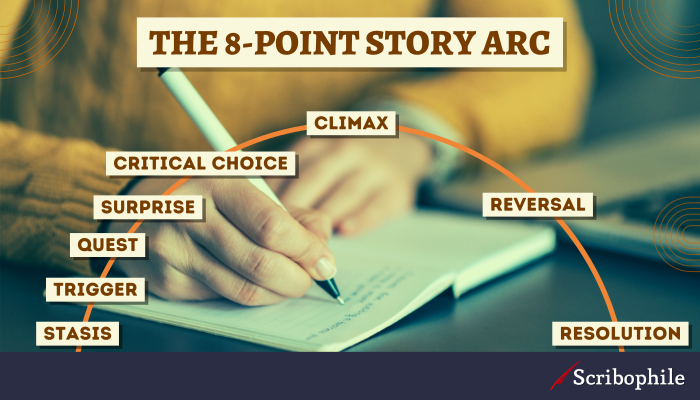

The eight point story arc is a narrative framework made up of eight stages that should occur in a story, in a specific order, in order to create an engaging plot that feels natural yet riveting to the reader. These eight points are: stasis, trigger, quest, surprise, choice, climax, reversal, and resolution.

While some story arcs only have three or four points (like three act structures), this eight point arc breaks your plot down into even more definable plot points, which can be very helpful if you find yourself struggling with knowing where to go next with writing your story.

The eight points are…

-

The point of stasis

-

The trigger

-

The quest

-

The surprise

-

The critical choice

-

The climax

-

The reversal

-

The resolution

Here’s how each of these look in action.

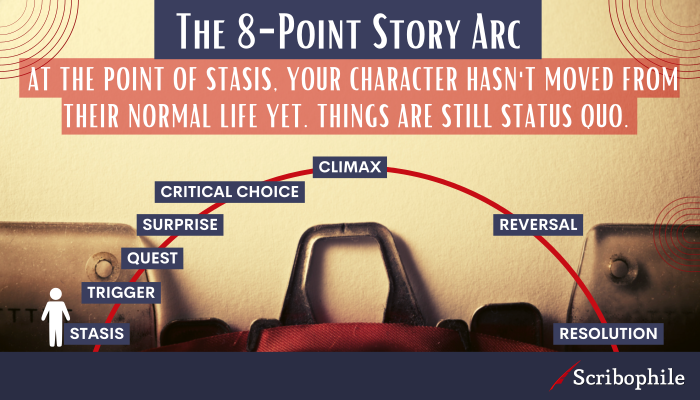

The point of stasis

Think of the beginning of most stories or favorite movies. Most start off, from the very first page or scene, with a character living their normal life. It’s all status quo, right? That’s what the point of stasis is. It generally involves the calm before the storm, the normal before your protagonist’s life gets all messy.

In other story structures, this is often called the exposition.

In The Lion King, the point of stasis is when Simba is just hanging out with his dad and friends. He’s enjoying life in the African savannah. He just can’t wait to be king. Everything is totally okay and nothing bad has happened yet.

The trigger

But then comes the trigger. Sometimes this is also called the inciting incident. It’s the thing that kicks off your plot and begins the upward trajectory of your story.

In The Lion King, that trigger would be Mufasa’s death. After all, Simba’s life would have likely never changed had Mufasa not died. Mufasa had to die in order for Simba to then go on his life-changing adventure and, later, reclaim his throne.

When the trigger occurs, it doesn’t always need to be something negative (even though it often is, for dramatic effect). In other stories, the trigger can be something good like a new opportunity, a new friendship, a new job.

The point is, the trigger changes your character’s life irreversibly and kicks off the rest of the story’s events.

The quest

The quest is exactly where that trigger sends your hero. Things begin to happen and now they’re responding by choosing to head out into the great unknown. For many writers, they’ll spend the main bulk of their word count in the quest.

During the quest, your protagonist is discovering who they are and the ramifications of that prior inciting incident or trigger. With the protagonist pursuing a goal, they’re having adventures (albeit small-scale adventures that don’t really compare to the dramatics ahead of them). Character development happens.

In a three-act structure, this would be called the “rising action” and kicks off the second act.

If we’re looking at Simba’s story again, his quest comes when he runs away from Scar and his home, and finds himself growing up with Pumbaa and Timon, eating slugs and beetles in a whole new world. He’s having a great time and learning about himself, but, again, none of this would have happened had Mufasa not died.

The surprise

But then, after your character has been questing for a while, enjoying themselves in their post-trigger world, a surprise comes along which introduces a new and unexpected conflict.

For Simba, that moment was Nala’s reappearance years later. She’s come to tell him that Scar has taken over and things are bad—real bad. This leads to…

The critical choice

The surprise and the critical choice part of your story are both relatively short, but oh-so-important to the plot.

The fifth of the eight plot points, the critical choice is when your main character is forced to respond to the upheaval that’s interrupted their quest. Now, they have to do something and, often, they have to do something quick, or bad things will happen.

In Simba’s case, he has to make a critical choice to either stay in his newfound home in comfort or follow Nala back to his family to save them from Scar’s wrath. This usually happens about half way through the story.

The climax

After your character makes their critical choice, it leads to the climax and their greatest obstacle yet. Simba decides to return to his family and that leads to the climactic moment of conflict where Simba fights with Scar.

The climax is the highest point of your plot, the thing all the action and tension have been building up to. Think of it as the apex of your story.

The reversal

And while some popular belief suggests the story naturally ends after the climax, there’s actually one other seventh step before we get to the end: the reversal. The reversal doesn’t need to take up a lot of space in your story, but it does need to be there.

The reversal is a change, a shift, a dramatic reaction to the climax. Maybe this reversal happens internally, as your main character’s viewpoint changes or they finally learn an important truth.

Maybe this reversal happens externally, like it does in The Lion King, as Samba’s life changes forever. He doesn’t go back to living in the rainforest and eating grubs with Timon and Pumbaa. He stays with his family and takes over his reign as king.

With the reversal, things are markedly different from where they began.

The resolution

And, finally, we have the resolution, where your story ends and things get back to normal (or, at least, as normal as they can be within your character’s new reversed world and setting). This is your opportunity to show “the new normal” and how your main character is settling in. Often, you can combine the reversal and the resolution into one scene.

How to use the eight point arc effectively

The eight point arc can be used for novels, short stories, film scripts—any sort of medium that relies on being able to tell a good story. So how can you write the eight-point arc effectively? Here are a few suggestions.

Think about your arc before you start writing

Whether or not you’re a plotter, pantser, or somewhere in between, thinking about your eight-point arc before you begin writing can ensure that you keep your story on track, going where it needs to go (rather than letting your characters wander aimlessly, losing your readers’ attention in the process).

If you don’t like to outline in advance, you don’t have to. However, it can be useful to keep the eight points in sight as you draft, so you know where you need to go next to keep your story following the arc. You don’t need to know what exactly the trigger will be, but you do need to keep in mind that you need to cross it to reach the rest of the story.

Reverse outline your story using the arc after you finish drafting

But let’s say you’ve already penned that first draft. How can the eight-point arc be useful to you now?

As you dive into revisions, consider reverse outlining your story. A reverse outline is an outline that you create after a story is already written. Instead of creating an outline and then ensuring your story follows it, you read your story and then create an outline that reflects your writing.

Look at how the outline represents your story’s existing flow and arc, and compare that outline to the eight point arc. Are you more or less following it? Or do you need to move some things around or add in some extra scenes, or even cut a few, to get your story back on track?

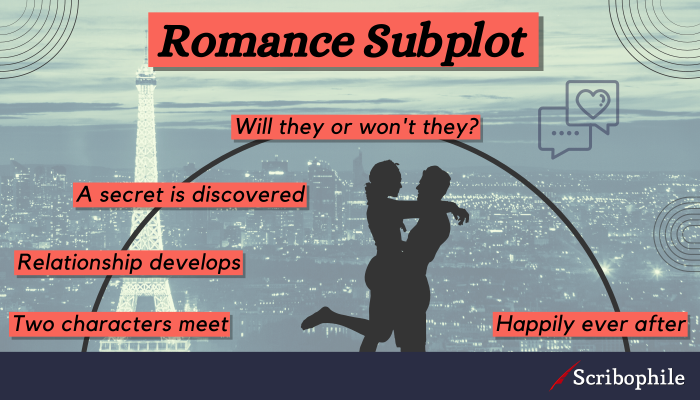

Realize that multiple arcs can coexist within one book

The eight-point arc is most helpful for organizing and outlining your story’s main, overall arc. However, as most writers, readers, or just general TV and movie fans will know, a good story usually has more than one plot.

Beyond your primary, main plot, you can also have internal character arcs, relationship arcs and character arcs for multiple protagonists or secondary characters.

These arcs do not need to be as complex as your story’s overall, main plot, but they should still follow that arc-like shape of rising in action to a climax and then settling into a new normal at the end of the story.

Books that include a romance subplot exhibit this well.

While the main event may be a daring adventure or hilarious heist, the romance subplot follows its own beats, with a trigger (two characters meeting), a quest (the relationship developing), a surprise and critical choice (say one of the characters finds out the other is hiding a terrible secret) and then a climax (will they or won’t they stay together?) before things settle into the rest of their lives (the happily ever after).

Combining multiple arcs—while still ensuring your main arc is at the forefront—can give your story immersive layers that grip readers every page of the way.

Use the eight point arc to keep your story headed in the right direction

While every story is different, every story does have a beginning, middle, and end. The eight-point story arc can help you keep your next great novel on track and avoid any dreaded bad writing snags, whether you’re in the outlining, writing, or revising stage.